MediaSmarts is a non-profit charitable organization that creates educational resources to help Canadians of all ages strengthen their digital media literacy skills. In addition, MediaSmarts is leading the campaign to create a national digital media literacy strategy for Canada and conducts the country’s longest-running study of youth experiences online, Young Canadians in a Wireless World. In this conversation, Faun Rice, ICTC’s Manager, Research & Knowledge Mobilization, speaks with Kara Brisson-Boivin, Director of Research at MediaSmarts, about the organization’s work and the most pressing priorities for fostering better digital media literacy in Canada.

What are mis- and disinformation?

Misinformation is incorrect, out-of-context, or misleading content shared by accident. For example, if I like a story about a dog heroically rescuing civilians without checking to see if it is true and my friend reads it, I have spread misinformation. Disinformation is created and distributed more purposefully—for example, spreading the wrong date of an election in order to change voting results. Mis- and disinformation can have dire consequences and are a pressing area of concern for contemporary digital media educators, policymakers, designers, and consumers.

What is digital media literacy?

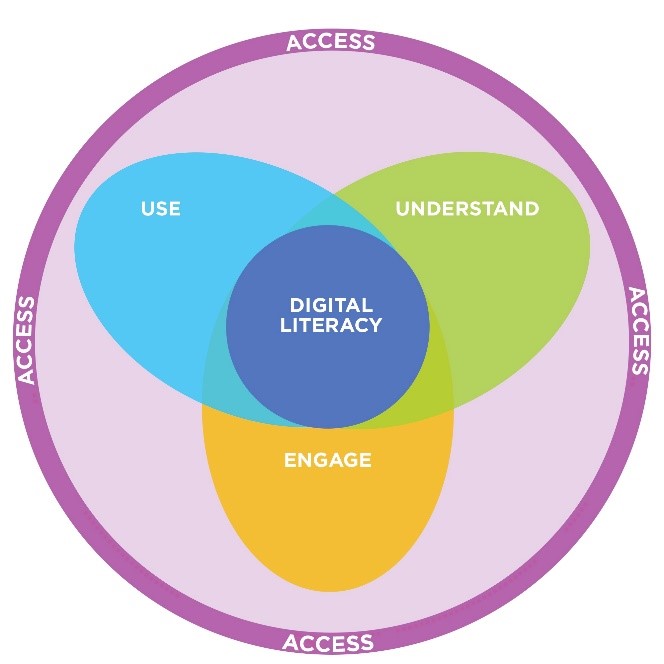

“MediaSmarts considers digital media literacy to be a collection of skills and competencies, beginning with adequate access to communications technology and the internet. Formally, MediaSmarts defines digital media literacy as the ability to critically, effectively, and responsibly access, use, understand, and engage with media of all kinds. “Without access, everything else is basically impossible,” Kara explained, adding that the type of access you have can impact your digital media literacy skills. “If your access is primarily—or only—through a smartphone versus a tablet or computer, your capacity to engage in creation or understanding are already limited. So, access is both things like bandwidth and the kind of device you have but also how these variables impact your ability to use, understand, create, and engage with digital media.”

MediaSmarts Digital Literacy Model

The Venn diagram reflects that use, understanding, creation, and engagement are each distinct but essential. “You can be really, really great at creating videos and sharing videos but missing the critical thinking piece. Or conversely, you can be a really avid critical thinker but struggle to have any idea of how to get on Twitter or TikTok. We wanted to be able to demonstrate that digital literacy is having competencies across all of these domains.”

What do young Canadians think about digital media literacy?

Kara’s team runs Young Canadians in a Wireless World (YCWW), a long-term research program that studies the experiences of young people online. Kara offered a few findings from the study (the first quantitative report from Phase IV of YCWW, which examines Life Online, will be published in October). First, young people are aware of protective surveillance but are not always comfortable with it. “There’s a lot of push and pull for young people around adult surveillance online. Whether it’s teachers or parents, [surveillance is] of course coming from a place of trying to be protective and helpful. Young people consistently tell us that they want to know that their parents or a guardian or a teacher have their backs but are not constantly looking over their shoulder.” Youth as young as nine or 10 in the study were very aware of classroom surveillance, for example: “We heard anecdotes in our focus groups where youth would type ‘Hey teacher or other adults listening’ in a Google Doc assignment because they knew it wasn’t a private space.”

Youth were also aware of the primary commercial purposes of the sites they used regularly and that they belonged to businesses using features like targeted ads. “They’re very aware that a lot of these platforms, about 90% of them, are corporately run and driven. But they are also like, ‘Well, what else am I supposed to do? If I want to socialize with my friends, if I want to do research for a project, this is where I have to go.’”

And finally, the upcoming reports (like previous phases of the study) will contest the stereotype that young people aren’t concerned about their online lives. “Young people are concerned about things like how much time they spend on screens. What they do on screens. They’re very concerned about their privacy. They’re very concerned about other aspects of their wellbeing.” But, Kara explains that online communities—for learning, connection, events, on- and offline gatherings—are inextricable from most young people’s lives. This makes it all the more important that young people are supported as they build and maintain their digital wellbeing.

In terms of critical issues in digital media literacy curriculum, how do you verify a source?

Given the findings from the YCWW study, I asked Kara for her “number one” digital media literacy skill she would like to see integrated more fully into Canadian curriculum. From both youth and parental perspectives, she said it was authenticating and verifying information: “We heard that loudly in the Young Canadians study.” This finding was interestingly consistent with research conducted by MediaSmarts in 2019, where parents cited mis- and disinformation as their top concern. “Something like 80% of parents were worried about misinformation.”

MediaSmarts has several public campaigns to teach all ages how to verify information. “We have one called ‘Check First, Share After.’ The idea behind that is to pause; don’t just read a headline and then send it off back into the internet.” Kara explained that one of the biggest and most important pieces of digital media literacy is to recognize is that everyone is now both a consumer and producer of information. While traditionally, a newspaper would come directly to a reader, “today, consumers can easily share any kind of article, piece of information, tweet, whatever, to endless numbers of people. And that just changes the entire dynamic. Whether we like it or not, responsibly, all of us to take some steps before we are contributing to this sort of tidal wave of information that we’re all having to sift through.”

MediaSmarts’ Break the Fake campaign also addresses fact-checking by giving viewers four steps to check a piece of content. The first is to use fact-checking tools such as Snopes and other experts. The second step is to look for the original source of the information. This could be present in a link or might require some search engine work to see where the story originated. The third is to verify the source. Kara gave an example of a story in the Globe and Mail. “Presuming we didn’t know what that [news organization] was, you could search Google or Wikipedia to see if the Globe and Mail is a real news outlet, with a good track record.” A fourth test is to search if other news outlets are reporting on the same story and if news outlets with different political views are reporting the same story.” MediaSmarts offers a workshop and resource series on fact-checking based on these four key steps.

What would a digital media literacy strategy for Canada look like?

MediaSmarts recently launched an effort to create a digital media literacy strategy for Canada. Kara spoke about what this could mean and gave international examples. “The UK developed a strategy that is grounded in some of the key online harms that we are all facing today, primarily mis- and disinformation and online hate. They did an extensive mapping exercise where they looked at all of the different community organizations, academic departments, and other groups that are doing digital media literacy work broadly.” The strategy is “housed” in the U.K. government’s Department of Digital, Culture, Media and Sport, which Kara noted gives it longevity and leadership. After mapping over 170 organizations, the team behind the UK strategy and worked collaboratively to research and create digital media principles and benchmarks to work toward.

In Canada, Kara said that MediaSmart’s digital media literacy strategy is still in search of a government home. “That’s not to say that it’s something we think can only live in one department. We definitely need leadership, and digital media literacy needs a home, but we kind of see it like gender-based analysis (GBA+), where every department (and every funding call) needs to be asking, ‘How does gender fit here?’ They also need to be asking, ‘How does digital media literacy fit here?’”

Another dimension of creating a national strategy is identifying benchmarks or measurements—for example, to assess Canadians’ digital media literacy skills at different ages. When I asked Kara if Canada should be aiming for an international standard for comparison with the rest of the world, she acknowledged that the OECD has measurements in place but that she considers them very Eurocentric. “We are really advocating for a system that is designed and built in Canada, for Canada. Intersections with digital equity and inclusion and closing digital divides is really core to this work.” In a Canadian context, building digital media literacy competencies and measurements means “consulting with Indigenous communities, newcomers, and non-English speaking persons among others who have specific needs to be considered in building a strategy, in defining what digital media literacy is, and deciding how we will measure the success of that work so that we can make sure that whatever benchmarks or competencies we design are equitable.” The last thing we want to do, Kara said, is build a model that disadvantages people who are already facing digital inequities. To learn more about the work that MediaSmarts has done on the national strategy, readers can consult its report From Access to Engagement.

How can people get involved?

In order to promote digital media literacy and ongoing research, education, and advocacy across Canada, MediaSmarts will be hosting the 17th annual Media Literacy Week from October 24-28. Virtual talks and panels will be taking place, including a research event featuring a public talk and student panel that addresses online harassment researchers face in publishing and mobilizing their research findings. In addition, this year, MediaSmarts is launching the first ever Digital Citizen Day, a day to set aside and reflect on being an ethical digital citizen. Readers who are interested in getting involved can get in touch with MediaSmarts to become a Media Literacy Week collaborator, or learn more about the digital media literacy strategy by reaching out at @email. Finally, the website contains information for teachers and parents who want to use digital media literacy education resources.

Kara Brisson-Boivin, PhD, is the Director of Research for MediaSmarts. Kara is responsible for the planning, methodology, implementation, and dissemination of key findings from original MediaSmarts research studies as well as evaluations of MediaSmarts programs. Kara also holds an appointment as an Adjunct Research Professor in the Sociology Department at Carleton University. Kara works with a number of partners (on tri-agency funded projects, in private and public sector organizations, and in federal government departments) on online issues, including digital well-being, digital citizenship, digital equity and inclusion, privacy, hate, activism, and algorithms and artificial intelligence. Kara has published extensively in academic journals, magazines, news op-eds, and research blogs. She also has a background in presenting research to key stakeholders on parliamentary committees and at academic conferences. Kara is regularly invited to talks, panels, media interviews and to present keynote addresses.