ICTC Overviews summarize findings from full-length studies. To read the original report, visit it here.

Study Scope

This third ICTC edtech report expands on previous research into distance learning in Canada. It elaborates on opportunities and challenges of edtech adoption and provides a planning framework for the long-term adoption of distance learning in the education system.This study includes interviews with education subject matter experts from across Canada and a survey of 1063 Canadian students and parents, and also considers distance-learning among Black Canadians, Indigenous youth, and people with disabilities.

Study Context

Distance learning has a long history in Canada, but online learning capabilities have greatly accelerated its adoption in recent years, particularly during the COVID pandemic.

Canadian distance learning reaches back to 1889 when McGill University began offering distance learning degree programs to teachers in rural Quebec.

- By 1912, the Universities of Saskatchewan and Alberta followed suit

- In 1921 marked the beginning of grade school distance education in the province

- In 1941, the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, Canadian Association for Adult Education, the Federation of Agriculture, and St. Francis Xavier coordinated a series of radio broadcasts and materials for living room study groups

- In 1972, the Athabasca University in Alberta became an entirely distance-based school that, at the time, relied on printed course materials and student-tutor interaction via phone

- The 1980s saw the introduction of broadcast educational content via satellite and television in partnership with TVOntario, Radio-Québec, the Saskatchewan Communications Network (SCN), Northern Canada Television, and ACCESS Alberta.

- The 1990s and early 2000s saw the arrival of the internet accelerated distance education. Colleges formed consortia to share costs and develop online resources (e.g., in 1995, OntarioLearn pooled resources of 24 colleges to become one of the larger college level course providers in North America). Other organizations often hosted internet services for their participating colleges, offering course development assistance, single source access learning portals, and extensive marketing. In secondary schools across the country, a surge in adoption of online learning management systems (LMS) occurred the early 2000s.

Key Findings

For distance learning to be a truly viable option beyond emergency education, it needs to engage and empower students while overcoming the challenges of equitable access, social isolation among students, and uneven technological competencies of educators.

Previous ICTC edtech reports discuss the need for educator training and competencies. This research finds technological competence, professional development, educator and parental support, and infrastructure readiness to be among the most significant predictors of success in both emergency and ongoing distance learning scenarios.

Study Findings

COVID-19

Prior to the pandemic, there was a wide range of participation in K-12 distance/online learning. Depending on the province it could be under 1% up to 11%.

As of 2021, more provinces resumed full in-class learning. Some provinces, British Columbia, for example, view online learning as a “classroom alternative,” which represents a shift away from emergency distance learning and a return to standard learning.

The Growth of e-learning Tools in Canada

Between 2011 to 2015, distance learning activities in higher education, which includes self-paced e-learning programs, saw a 58% increase (approximately 11% annually) in enrolment.

Prior to the pandemic, the number of postsecondary institutions in Canada developing e-learning content increased at a rate of 2% per year.

- Interviewees noted that support and training have a direct impact on an educator’s level of competence with e-learning tools, which also may impact investment decisions

- Nearly two-thirds of Canadian postsecondary institutions indicate that e-learning technology is now fundamental (K-12 data is not available)

- Larger postsecondary institutions believe e-learning integration can foster innovation and enable institutions to better respond to changing government policies

Common Technology tools

Interviewees noted the most familiarity with the following technologies:

Learning management systems (LMS) such as D2L, Moodle, Blackboard, Canvas, PowerSchool, and Seesaw. These systems (or engines) are used

- to manage course-related content, communications, and administrative tasks (e.g., performance tracking and reporting)

- can be web-based or locally operated applications

- LMS tools have become increasingly sophisticated in their use of big data, creating an opportunity for educators to expand their skills and understanding of basic analytics to better leverage these skills

- LMS analytic capabilities help educators monitor student engagement and participation levels

- Video conferencing services, such as

- Zoom and Kaltura

- Adobe Connect, Google for Education, Office 365 for Education, and Articulate 360 can be tailored to education as well but were mentioned less frequently

- Tools such as Adobe Connect 11 were noted as particularly helpful because of their accessibility-focused design to aid students with mobility, vision, and hearing barriers

K–12 Students and Their Parents

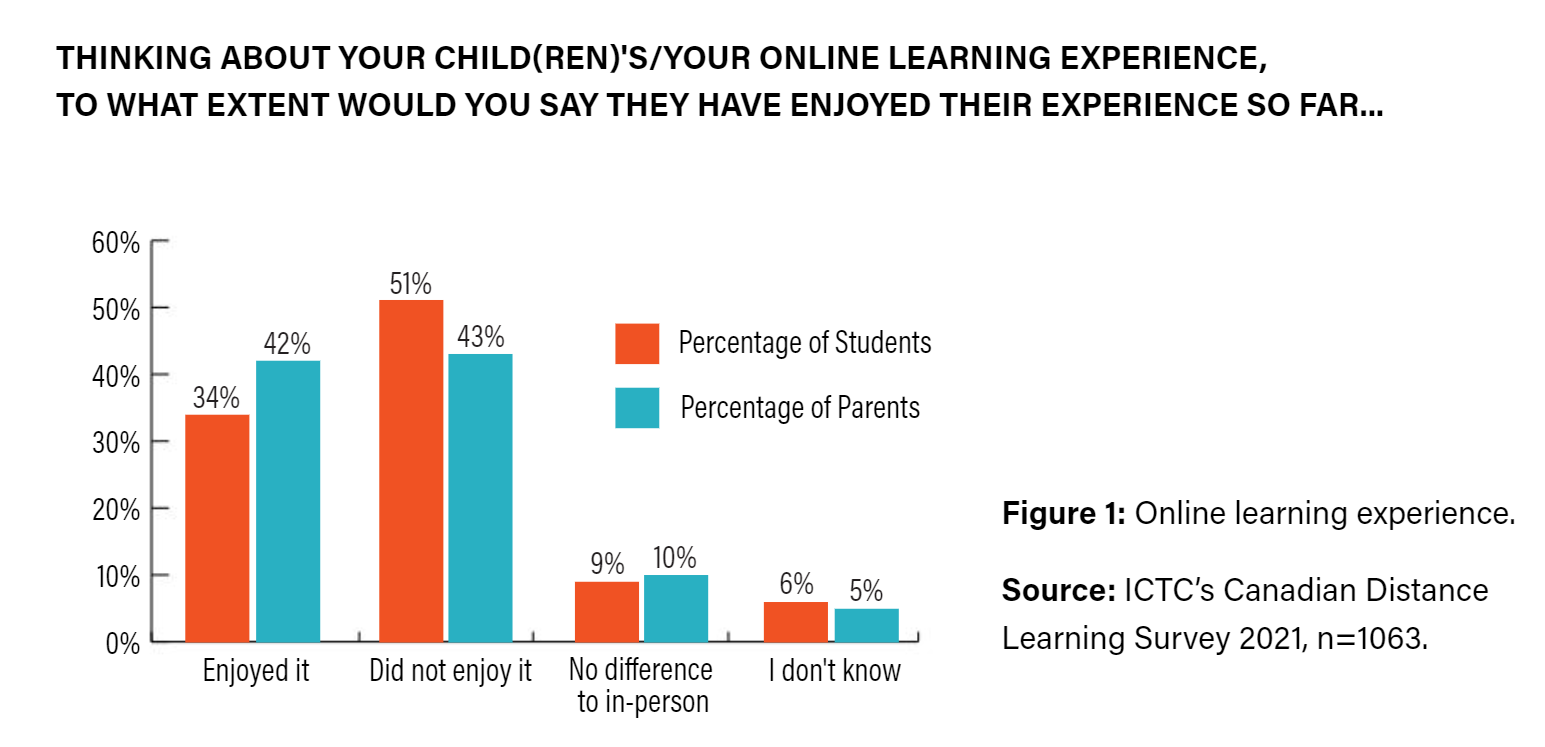

ICTC’s survey of students and parents asked some of the following questions:

ICTC’s survey suggests that improvements to K-12 online learning would benefit from stronger infrastructure investments:

- Notable challenges to distance learning highlighted the need for support and communication with students and their families

- Permanent e-learning would need to address these issues by hiring for these roles

- Added responsibility and pressure faced by educators in troubleshooting technical challenges could also be mitigated by this additional support

- Successful examples noted by interviewees were educator assistants (EAs) with strong digital skills for K-12 educators

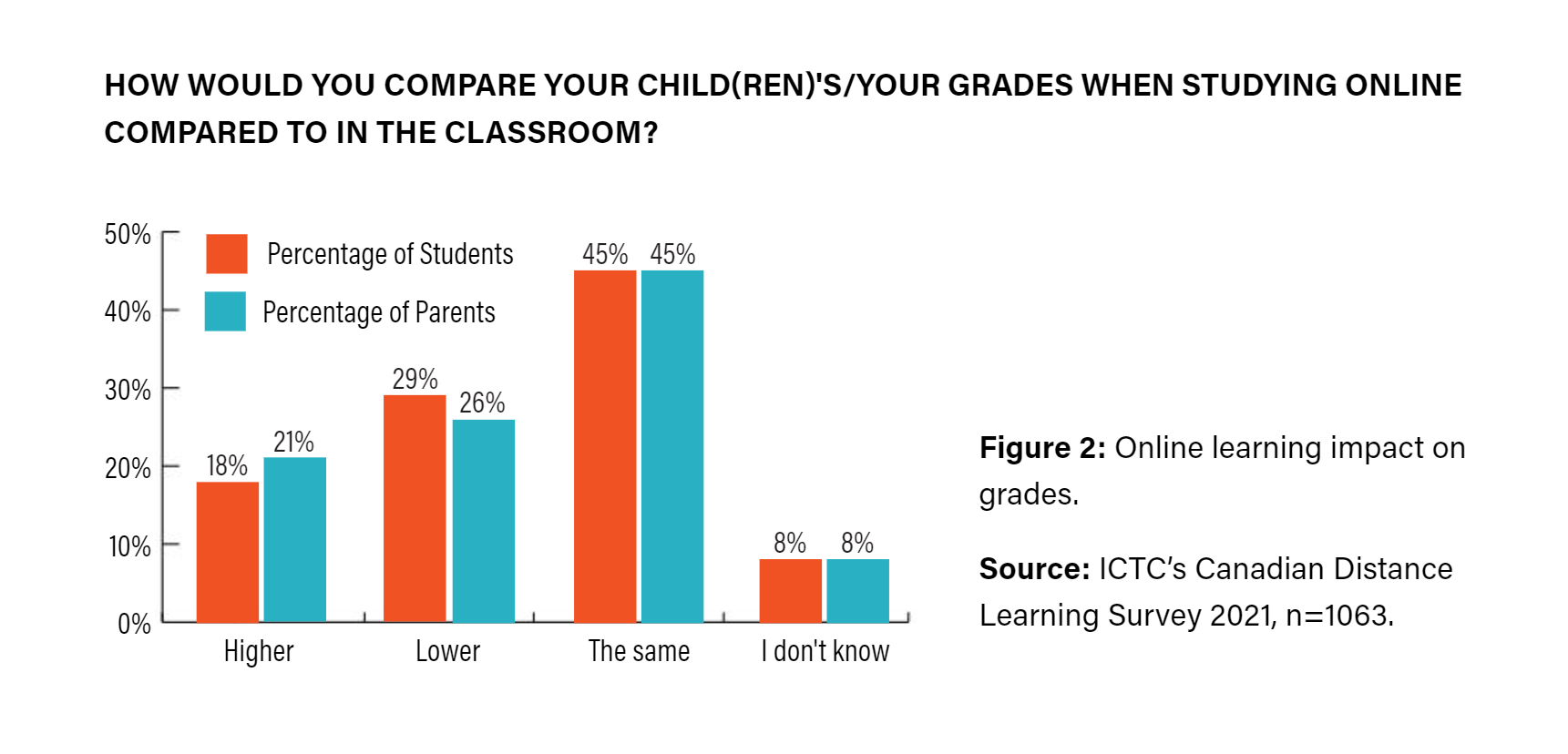

K-12: Academic Performance

Several school boards across Ontario, Quebec, and Alberta reported an overall drop in academic performance during COVID, and many people linked this outcome to the shift to online learning.

A recent GALLUP survey suggests that other criteria beyond grades should be considered when evaluating online learning.

- Only 11% of parents and 1% of teachers selected “getting good grades” as among the most important learning outcomes for students

- Critical thinking, curiosity to learn independently, and problem-solving skills were the top three learning outcomes selected by teachers and parents

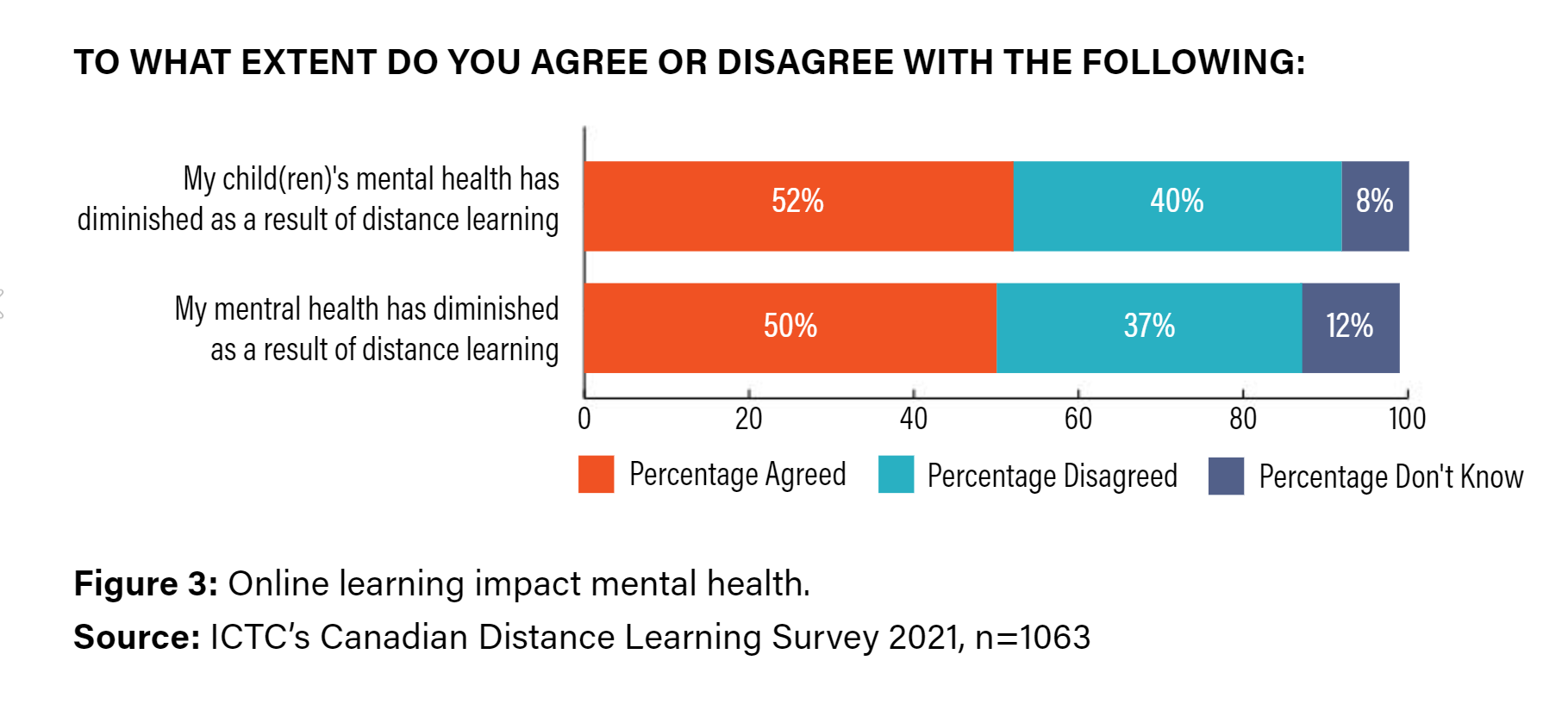

K-12 Impacts to Mental Health

Emergency distance learning spawned significant worry, stress, and anxiety for students.

A recent US Center for Disease Control and Prevention study suggests online learning potentially poses more risk to the mental health and wellness of children than in-person learning.

- About 25% of children ages five–12 who received virtual instruction or combined in-person and virtual instruction reported a worsened state of mental or emotional health (compared to 16% of children who received only in-person instruction)

- UNICEF, however, found the impact of screen-time on the mental health and well-being of children is “very small”

According the ICTC survey of parents and students, distance learning during the pandemic had a greater impact on the mental health of older students.

- Ages 17-23 and 24+ reported 65% and 66% diminished mental health respectively (vs 50% of all surveyed students)

Choice of whether to study online or in-person plays a role in mental health.

- More than 50% of students who studied online due to provincial mandates felt their mental health had diminished

- Compared 43% of students who studied online by choice

Parents’ perspectives on their children’s mental health.

K-12: The Widening Digital Divide

COVID-19 accentuated the digital divide, calling greater attention to disparities and inequalities of internet connectivity and access to technology.

- 83% of all students reported that they had the technology required to study from home vs 79% in rural locations

- 28% of parents reported their children did not have their own computer and needed to share devices with other members of the family (particularly in rural areas and among students in low-income families)

- 28% of all parents, compared to 38% of parents living in rural areas, could not support their entire family’s working/studying online at home due to poor internet connectivity

K-12: Online Learning “Age and Stage”

KINDERGARTEN TO GRADE 3

During the 2020-21 academic year, educators were challenged to provide age-appropriate online opportunities to develop basic digital literacy skills in this age group.

- Educators who were required to teach remotely often opted to connect synchronously using videoconferencing technology to interact directly with students, avoiding the use of other tools that required a higher degree of digital skill

GRADES 4-8

For older children, distance learning offers distinct advantages.

- Personalization of digital learning is particularly important

- As confidence and exposure to digital tools increases, students can develop their own learning preferences aided by software flexibility

- Adaptive Learning Systems (ALSs), for instance, help foster innovative, analytical, and critical thinking as well as creativity at an accommodating and flexible pace

GRADES 9-12

Students in senior K–12 years are typically already comfortable using technology in educational settings.

- Distance learning is easier for this age group because of their accumulated digital literacy skills and ability to concentrate

- In 2020, a US survey of high school e-learning determined that augmented, blended, or fully online classes were likely to become the new standard in education

POST-SECONDARY

Although many universities offered some of their academic programming online prior to the pandemic, approximately one-quarter of students had their classes either postponed or cancelled entirely in 2020.

- ICTC’s survey indicates about 50% of post-secondary students viewed in-person learning more positively than emergency online learning

- Despite an increase in take-home assignments, about 33% of students of age 17 to 23 and 25% of students of age 24-plus felt that their grades had improved

Students with Disabilities

Early in the switch to emergency online learning, research identified students with disabilities as most vulnerable to feeling disconnected from their peers and insufficiently supported.

- The change of routine and lack of in-person dedicated support and access to specialized services could cause regression or delayed learning progress

- Online learning tends to shift learning responsibilities to the families of students with disabilities

Learning technologies, however, also present opportunities for students with disabilities.

- Platforms such as Zoom, Brightspace, and TopHat include accessibility features like external text-to-speech software, screen reader support, closed captioning, and accessibility checkers

- Adoption of specific technology-based tools to assist students with disabilities include

- Dictation/text-to-speech tools

- Executive/time management tools (such as Cold Turkey to block websites and applications or Priority Matrix to coordinate project needs)

- Accessible screen readers such as the NVDA, NonVisual Desktop Access

Indigenous Youth Experiences with e-learning

In Ontario at the end of 2020, only 17% of households on First Nation reserves had access to broadband internet connectivity.

- E-learning disproportionally places barriers on Indigenous families due to poor internet connectivity

- Where connectivity is available and sufficient, Indigenous educators feel that a growing reliance on technology coupled with the lack of culturally embedded course content is a cause for concern

- This includes fears about digitally sharing, recording, and presenting Indigenous knowledge without the consent of the creators

- Recording a community’s customs, protocols, or stories with community elders and knowledge keepers without consent is considered not only as culturally insensitive but also an infringement on Indigenous intellectual property rights in Canada

When consent is granted, however, opportunities for widespread learning about Indigenous content were encouraged.

Black Youth Experiences with E-Learning

According to a report published by the African-Canadian Civic Engagement Council, Black Canadians are more likely to have had their household finances negatively impacted by COVID-19, limiting the resources available for education.

- Stats Canada found that in January 2021 33% of Black Canadians were living in households where it was “very difficult” to meet basic financial commitments

- Black parents with young children also faced additional hardships related to prolonged school closures, childcare costs, and higher hardware and connectivity fees due to e-learning

Access to technology and mentorship initiatives play critical roles in advancing outcomes for Black communities.

In developing long-term distance learning policies, provincial governments are encouraged to work with Black-led organizations at both the national and provincial levels.

Collaborative policy development can help ensure that the experiences of Black youth are represented in shaping long-term distance learning decisions.

Beyond COVID: Drivers of Online Learning in Canada

Educators need to look beyond simply transferring lessons online and transform their current practices.

TeachOnline.ca and Contact North offer guidance to achieving this pedagogical shift:

BLENDED LEARNING

- Both in-person and online instruction requires a review of classroom layouts, study goals, and interaction between students, educators, parents, and subject matter experts.

COLLABORATIVE APPROACHES

- Collaborative and active learning techniques allow students to share individual experiences and learn from each other in an instructor-facilitated environment

USE OF MULTIMEDIA AND OPEN EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES

- Open educational resources in various formats that enable students and instructors to access knowledge in different ways. Thousands of stand-alone educational materials can be accessed for free and leveraged to help facilitate new learning opportunities.

INCREASED STUDENT CONTROL, CHOICE, AND INDEPENDENCE

- Educators need to transition from selecting information for students to guiding students in locating, analyzing, and applying information relevant to certain topics.

- This degree of autonomy to the learner encourages them to use the best medium for their learning style

ANYWHERE, ANYTIME, ANY SIZE LEARNING

- The production of educational material in smaller segments and, if needed, with standalone credentials to accommodate the needs of students with personal responsibilities outside of the classroom

NEW FORMS OF ASSESSMENT

- Can include leveraging learning analytics, artificial intelligence, accreditation methods centred on student competencies, peer assessment, and various others for distance learning activities

SELF-DIRECTED AND NON-FORMAL ONLINE LEARNING

- Alternative learning solution enable students to access new interest areas independently without requiring facilitators

- Digitized progress tracking mechanisms and marking techniques can open new opportunities for students to learn at their own pace.

Recommendations for Bolstering E-Learning in Canada

The following recommendations adapted to different age groups and needs can be leveraged as a framework by educators, school administrators, and policymakers to spearhead and/or improve e-learning processes and polices in Canada across four pillars:

- Educator Support and Training

- Education System Transitions

- Equity and Inclusion

- Flexibility and Experimentation

1. EDUCATOR SUPPORT, EQUIPMENT AND STUDENT NEEDS

Minimum digital skills for educators are required to ensure a guaranteed level of quality in e-learning across Canada.

Educators should have access to core digital literacy skills development and the use of educational technologies according to age group.

- This should include any digital tool essential to facilitating online learning

- School administrators also need to select the most effective educational technology or digital tools for students

- Administrators need to evaluate the unique needs, economic and social circumstances of their student population

2. EDUCATION SYSTEM TRANSITIONS

Regional school boards and post-secondary school administrators will benefit from mandatory and standardized training on learning management systems.

This training will ensure a baseline competency across all educators while granting those with existing competencies an opportunity for added specialization.

- Well planned, coordinated, and executed e-learning strategies can help alleviate this pressure on caregivers at home

- Ministries of Education and district school boards should consider the development of support services designed for parents and caregivers of students enrolled in e-learning, such as

- Resources for one-on-one troubleshooting related to digital tools

- Individual lesson plans

- Equipment resources for those with limited access to digital tools

3. EQUITY AND INCLUSION

To effectively teach, engage, and empower all students, e-learning must be rooted in achieving equity and inclusion. The first step is to understand access.

- School boards and schools must consider what access students have to the hardware needed to participate in online learning

- Where access is insufficient, schools need to provide accommodations

- The average level of internet access in their region is an important consideration—in case of insufficient connectivity, schools should lend data-enabled devices or provide access to portable internet hotspots

Fostering improved equity and inclusion in online education means also acknowledging the unique circumstances and needs of students from different socioeconomic backgrounds, cultures, and ability levels.

Curriculum should be developed with consultation from parents and organizations that understand and support underserved students.

Students from Indigenous communities may have unique cultural education needs compared to Black students, and students with disabilities may require accommodations to succeed in learning online.

4. FLEXIBILITY AND EXPERIMENTATION

Educators must be able to also engage in active learning and student-centric learning activities with their students.

- To facilitate this, educators require the opportunity to customize and adapt the curriculum for students when learning online based on individual needs

- To facilitate troubleshooting and digital competency development, an online community of educators and IT professionals should be developed

For schools and school districts interested in testing a more robust digital environment, technology sandboxes can trial technology tools, instruction styles, and new teaching methods.

Digital sandboxes also allow educators to experiment with new programs and features. Successful trials can be scaled and permanently adopted.

ICTC Overviews summarize findings from full-length studies. To read the original report, visit it here.