This article was written ahead of the federal government’s throne speech of September 23, 2020. According to a recent Ipsos poll, 18% of Canadian respondents want to hear a plan to reduce the deficit, while 17% want to put together “a longer-term universal basic income [UBI] for all Canadians.”

This piece does not take a position on the efficacy or need for a UBI: rather, it reviews existing research and identifies further areas of investigation. Given the division in public opinion that currently exists in Canada, research into the outcomes of UBI-style benefits is an essential component of future policymaking.

On July 31, 2020, the Canadian federal government announced its plans to ease the impact of closing the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB), a program that provided a taxable income replacement for workers impacted by COVID-19. Former CERB recipients will be transitioned to Employment Insurance (EI) this fall. In addition, the announcement promised other types of benefits for people who do not qualify for EI, such as gig and freelance workers. The CERB is currently scheduled to transition out on September 26, 2020: accordingly, while this article employs the present tense to refer to the program throughout, most readers will be encountering this article after the benefit has closed.

In April of this year, we wrote about the CERB’s similarity to the idea of a UBI and the importance of gathering data on the CERB’s dissemination and impact. Given the dearth of data on UBI for large populations at the national level, with most pilot programs limited to small regions or sample sizes, the article argued that COVID-19 and its unique economic policy situation provided an unparalleled opportunity to gather data on the potential impact (and feasibility) of something like a UBI in Canada.

“The CERB is basically a guaranteed income itself, it really has all the hallmarks of a guaranteed income. But I think it has also opened a lot of people’s eyes who didn’t understand the need.” — Max Fawcett on CBC News, “Year K: A Canadian guaranteed income?”

Now September, the CERB program may be winding down, but UBI has made it into the Canadian federal Liberal caucus’ priority list.[1] As is always the case with new economic initiatives, supporters and detractors are currently lining up to share perspectives on whether or not a UBI is necessary, or feasible, in Canada. This moment in time is unique, however, in that all parties have the opportunity to use data from the CERB to understand important questions about the impact of a UBI on access to benefits, employment incentives, affordability, health and wellness, and myriad other topics. Given the CERB’s many similarities to UBI, data from its nearly half-year existence is crucial to assessing the role of UBI and other guaranteed income policy in Canada.

One of the central goals of UBI proponents is to ensure that no one who needs an income supplement is “left behind.” The universality of UBI is intended to remove issues of access, barriers to application, and stigma, among other challenges. We can now ask a similar question of the CERB: how effective was it as a blanket approach? As a somewhat targeted benefit (in that it was only intended for those who experienced a decrease in income due to COVID-19), does it illuminate whether or not a more universal program is necessary?

Accordingly, this article examines the literature and news released to date that answers the first research question identified in our previous article:

What populations are included in or excluded from the CERB? When the dust settles, what vulnerable communities were unable to access it? Why and how can those barriers to access be overcome in the future?

Who was the CERB intended for?

Eligibility was expanded in April 2020 during the CERB’s first few weeks of existence to include seasonal and self-employed workers, among other groups.[2] As it stands, CERB eligibility is determined by the following:

1. “He, she, or they must be a worker:

- at least 15 years of age; and

- a resident of Canada; and,

- for 2019 or in the 12-month period preceding application for the CERB, have had a total income of at least $5,000 from employment, self-employment, EI benefits, or other payments related to pregnancy, newborn children, or adoption.

2. Workers are eligible for the CERB if:

- they cease working for reasons related to COVID-19 for at least 14 consecutive days within the four-week period for which they are applying for the benefit; and

- they have not ceased work voluntarily; and

- they do not receive more than $1,000 of employment or self-employment income within those same four weeks; and

- they do not receive any EI benefits or other benefits related to pregnancy, newborn children, or adoption.

Those who apply for the CERB receive $2,000 for each four-week period, regardless of their total annual income.”[3]

Who Accessed the CERB?

The CERB emerged in response to severe job losses across the country. Statistics Canada estimated that employment dropped by 15% from February to late April 2020.[4] Using different sources and methods, other research teams found that in some provinces, more than one in five households experienced a job loss,[5] and that workers aged 20–64 years experienced a 32% decline in aggregate weekly work hours.[6] Many sources found that those most impacted by COVID-19 were employed in public-facing industries impacted by shutdowns, such as the service industry.[7] Indeed, 43% of those employed in the accommodation and food services sector applied for the CERB.[8]

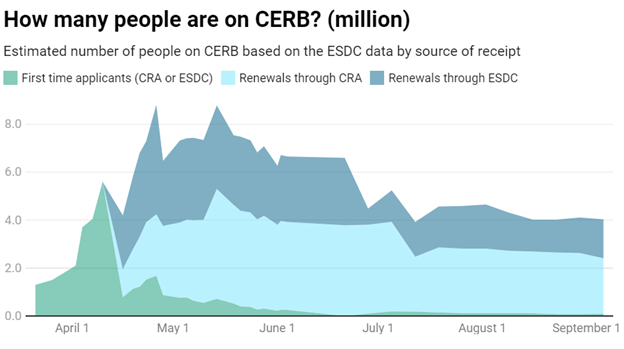

Figure 1: Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, ESDC data. From David Macdonald, “Transitioning from CERB to EI could leave millions worse off,” Sept 15, 2020. https://behindthenumbers.ca/20…

While the CERB is designed to be unilaterally applied and easy to access, it nevertheless faces some challenges in equitable distribution. For example, one study found that differences in provincial income assistance (IA) schemes and their interactions with the CERB means that recipients are treated asymmetrically depending on the jurisdiction in which they live.[9]

Age and Income

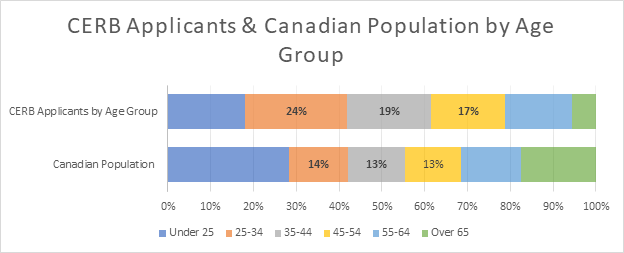

First, much has been made of the fact that the CERB has been disproportionately applied for by young people, as shown in Figure 2. This has created various reactions from the research and journalism communities. One existing analysis estimates the number of young CERB applicants who may not be in dire financial need (e.g., living with their parents).[10] Other sources have found that CERB applicants overall are likely to have suffered a substantial loss of monthly income and have lower household savings than non-applicants (though not negligible, often stored in RRSPs or TFSAs).[11] In addition, younger workers may be more likely to be employed in industries impacted by shutdowns, such as the food and beverage industry.[12] Accordingly, the jury is out on applicants’ household income by age until more data is available, and relying on proxies currently provides fodder for more than one perspective.

Figure Two: CERB Applicants vs. Canadian Population, a Comparison by Age Group. Sources: Canada Emergency Response Benefit statistics (last updated September 6, 2020, https://www.canada.ca/en/services/benefits/ei/claims-report.html) and Statistics Canada (2019 Data, Table 17–10–0005–01), figure by ICTC.

Seniors

While working seniors are eligible for the CERB (which is not impacted by pension income), many senior citizens are accessing different types of benefits such as Old Age Security and the Guaranteed Income Supplement. During the pandemic, several fraudulent schemes targeting seniors emerged — accordingly, policies must weigh the benefits of application-based support vs. more secure automatic payments.[13]

Students

Students who do not qualify for CERB or EI, possibly due to lack of prior income, may access the Canada Emergency Student Benefit (CESB) if they are unable to find work.[14] Several student groups have noted that they receive many questions about eligibility, suggesting that applicants are confused about which of the benefits to apply for. In addition, International students may qualify for the CERB, but not for the CESB.[15]

Gender

During the early months of the pandemic, the Government of Canada’s Gender-Based Analysis Plus (GBA+) of the CERB found that women’s employment losses were slightly higher than men’s (February to April 2020, 17% vs. 15%, respectively). However, men’s employment increased at over twice the speed of women’s during reopening in May.[16] The GBA+ analysis suggests that this could be due to the increase in goods-producing industries, more commonly staffed by men, and/or women’s likelihood of shouldering caregiving responsibilities during school disruptions. The Canada Recovery Caregiving Benefit (CRCB) is intended to support workers who quit their jobs to care for a family member or child after the dissolution of CERB, and while women are expected to access this more frequently than men, it is possible that women’s careers will thus be disproportionately impacted in the long term.[17]

An early flaw in the CERB’s application process meant that women who self-identified as pregnant on an EI application were left on EI, rather than being transitioned to CERB, potentially impacting their parental leave time.[18] This error was resolved on May 8, 2020.

Indigenous People

A report from July 2020 noted that 13.4% of off-reserve Indigenous people were receiving the CERB, vs. 18.7% of non-Indigenous people, despite comparable employment losses.[19] Other types of financial aid, including funding for off-reserve Indigenous services organizations[20] and funding for Indigenous students[21] has been issued. This topic merits further investigation, both into the reasons for disproportionate access and mitigation for the future.

Nationality and Citizenship

Migrant workers, women, and newcomers were more likely to experience low job security during the pandemic.[22] There were disproportionate rates of newcomers among CERB applicants,[23] and temporary foreign workers and seasonal workers are able to apply for the CERB so long as they meet other eligibility criteria. In addition, unlike means-tested social assistance payments, accessing the CERB will not prevent a newcomer from sponsoring family members to come to Canada.[24]

Key Takeaways:

First, the federal government has responded quickly to most reports of inequitable access. Throughout the pandemic, when a group was identified as CERB-applicable but, for some reason, was ineligible or had difficulties accessing the benefit (e.g., pregnant women, the self-employed, seasonal workers), the federal government, in most cases, responded by expanding eligibility criteria, resolving an error, or providing an alternate benefit.

However, there are still some signs that not all groups were able to understand and apply for the CERB. Despite the CERB’s relatively “universalist” approach and the best efforts of policymakers to make it accessible to everyone in need, it has shown some signs of unaddressed inequitable access. From some reports, this seems to be the case for off-reserve Indigenous Canadians and possibly international students. More data will be needed to verify these, identify other groups for which this is the case, and mitigate this issue in future.

The CERB has overlapped in unforeseen ways with benefits in different jurisdictions and other types of benefits. This is also likely to be the case with the benefits designed to replace the CERB. Alternate and overlapping benefits may result in greater long-term asymmetries in recipients. This is particularly challenging given Canada’s many overlapping jurisdictions, where even a universal federal benefit may interact unevenly with provincial benefit schemes. Further research is required to understand the full impact of such asymmetries (as opposed to the benefits of easy implementation).

Next Steps

The CERB’s attempt at universal access is not the only valuable case study policymakers can examine. The question of economic feasibility is already under discussion,[25] and many other questions will need to be addressed, along with the remaining research questions identified earlier in this series:

- What were the policy’s goals, and were these met? (E.g., due to pandemic closures and the difficulties of workforce re-entry, how did this policy’s goals differ from those of EI, the CCB, or other programs?)

- What impact did the CERB have on workforce participation during and after COVID-19 (even if it’s not possible to disaggregate from the effects of the virus), including impacts on job seeking, career changes, layoffs, entrepreneurship and innovation, and self-employment and gig economy participation? What other activities have people on CERB undertaken?

- How are we sustaining the CERB financially? What economic outcomes will this have? What might the economic outcomes have been without the CERB?

- How has the CERB impacted consumer spending? In what countries are consumers spending? What impact has the virus had on e-commerce, and what impact has this had on Canadian tax revenues?

- What outcomes do CERB recipients experience related to health, housing status, education, the aforementioned labour market participation and entrepreneurship, and financial status (e.g., debt)? How do these outcomes differ for the following people: individuals who undertake additional care work or have dependents, formerly self-employed or gig economy individuals, individuals by gender, individuals with very high or very low household incomes prior to the CERB, individuals who identify as Indigenous, individuals in rural or Northern Canada, or newcomers?

- How do the outcomes of Canada’s policy compare with those of other countries, such as Spain?

References

[1] Joan Bryden, “Guaranteed basic income tops policy priorities for Liberal caucus at upcoming convention.” CBC News, Sept 12, 2020 https://www.cbc.ca/news/politi…

[2] Department of Finance Canada, “Expanding access to the Canada Emergency Response Benefit,” https://www.canada.ca/en/depar…

[3] Gillian Petit & Lindsay Tedds, “The Effect of Differences in Treatment of the Canada Emergency Response Benefit across Provincial and Territorial Income Assistance Programs.” Canadian Public Policy, Vol. 46 (S1), July 2020, pp. S29-S43.

[4] Labour Force Survey, April 2020, https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/200508/dq200508a-eng.html

[5] Estimate from Quebec, “Snapshot of Households that Received the Canada Emergency Response Benefit and Paths for Further Investigation,” Cirano Perspectives/Insights, 2020 http://cirano.qc.ca/files/publ… p 2.

[6] Thomas Lemieux et al., “Initial Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Canadian Labour Market,” Canadian Public Policy, Vol 46 (S1), June 24, 2020, https://www.utpjournals.press/…

[7] Ibid.

[8] Government of Canada, “GBA+ Summary for Canada’s COVID-19 Economic Response Plan,” last modified July 15, 2020, https://www.canada.ca/en/depar…

[9] “For example, IA clients living in Golden, BC who receive the CERB will receive both their entire IA benefit and the full amount of the CERB, and only those who had earned over $2,000/month prior to the pandemic will see a decline in their total monthly income while receiving the CERB. However, persons living in Canmore, AB, less than an hour away from Golden, BC, will see their IA benefits decrease if they receive the CERB, potentially going down to zero in the months when they are collecting the CERB.” Gillian Petit & Lindsay Tedds, “The Effect of Differences in Treatment of the Canada Emergency Response Benefit across Provincial and Territorial Income Assistance Programs.” Canadian Public Policy, Vol. 46 (S1), July 2020, pp. S29-S43.

[10] E.g., “Distribution of CERB: Estimating the Number of Eligible Young People Living with Parents,” July 16, 2020. https://www.fraserinstitute.or…

[11] See Cirano Quebec Survey Data comparing the household incomes of CERB applicants and non-applicants. http://cirano.qc.ca/files/publ… Table 1.

[12] “The largest losses can be attributed to industries and occupations most affected by closures (such as public-facing occupations in accommodation and food services) and to workers who are younger, paid hourly, and non-union.” Lemieux et al., 2020, https://www.utpjournals.press/…

[13] Sarah Turnbull, “Seniors will have to wait another month for COVID-19 aid payment,” CTV News, June 4, 2020. https://www.ctvnews.ca/politics/seniors-will-have-to-wait-another-month-for-covid-19-aid-payment-1.4969086.

[14] Government of Canada, Canada Emergency Student Benefit (CESB), last modified Sept 17, 2020, https://www.canada.ca/en/reven…

[15] Catherine Cullen, “Some students still confused about emergency benefits, groups say,” CBC News, June 13, 2020, https://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/student-benefit-confusion-1.5610864

[16] https://www.canada.ca/en/depar…

[17] https://behindthenumbers.ca/20…

[18] Jordan Press, “Fix on Friday to finally let moms-to-be receive CERB, Qualtrough tells MPs,” CTV News, May 5, 2020, https://www.ctvnews.ca/politics/fix-on-friday-to-finally-let-moms-to-be-receive-cerb-qualtrough-tells-mps-1.4926056.

[19] Dylan Robertson, “Federal benefit access rate far from equal: CERB rate lower among urban Indigenous population,” Winnipeg Free Press, July 13, 2020. https://www.winnipegfreepress.com/special/coronavirus/cerb-rate-lower-among-urban-indigenous-population-ottawa-571749062.html.

[20] Teresa Wright, “Off-reserve Indigenous services to receive $75M boost amid coronavirus pandemic,” Global News, May 21, 2020, https://globalnews.ca/news/696…

[21] Jamie Pashagumskum, “Trudeau announces $75M in pandemic aid for Indigenous students,” APTN National News, April 22, 2020, https://www.aptnnews.ca/nation…

[22] Tyler Pacheco et al., “Job security and the promotion of workers’ wellbeing in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic: A study with Canadian workers one to two weeks after the initiation of social distancing measures,” International Journal of Wellbeing, Vol 10 (3), August 12, 2020, https://internationaljournalof…

[23] Government of Canada, “GBA+ Summary for Canada’s COVID-19 Economic Response Plan,” last modified July 15, 2020, https://www.canada.ca/en/depar…

[24] Jolson Lim, “CERB eligibility expanded to part-time and seasonal workers, Trudeau says,” iPolitics, April 15, 2020, https://ipolitics.ca/2020/04/1…

[25] Office of the Parliamentary Budget Officer, “Costing a National Guaranteed Basic Income Using the Ontario Basic Income Model,” Ottawa, Canada: April 17, 2018, https://www.pbo-dpb.gc.ca/web/…