This interview was originally conducted on September 30th, 2020.

Data science and artificial intelligence (AI) have made significant advancements in the last ten years, but there are a lot of questions arising about AI-driven decision-making processes in the public service. New Zealand is piloting an assessment tool that is opening the door to more ethical uses of AI by government.

Canada, New Zealand, and many other countries are working toward greater transparency and consistency in the way governments use algorithms to assist or make decisions. For example, both Canada and New Zealand have used a semi-automated process to triage visa applications and inform decision-making, prioritize applications, or assign risk to applications. While semi-automated decision-making can greatly improve administrative efficiency, it may also come with unintended consequences when it directly impacts human lives. Accordingly, both countries are now piloting new ways to assess and mitigate the risk that algorithms might pose, Canada with its novel Algorithm Impact Assessment tool, and New Zealand with an Algorithm Charter and the Risk Matrix within it.

In this conversation, Statistics New Zealand’s Dale Elvy and Jeanne McKnight share their role in developing the Algorithm Charter, the feedback they received along the way, and their plans for the future. Throughout the conversation, the team discusses some aspects that New Zealand has in common with Canada such as a commitment to Indigenous involvement, as well as differences such a size and jurisdictional structure.

Faun: Thank you both very much for joining us today! Let’s begin with introductions. Would you mind opening with a bit of an introduction about yourselves and your roles at Statistics New Zealand?

Dale: Kia ora koutou, I’m Dale Elvy, and I manage the System Policy team here at Statistics New Zealand. The System Policy team is part of the Government Chief Data Steward’s function within Stats New Zealand, and we work horizontally across a number of different departments and agencies to support them with regard to their data issues, as well as issues that impact public perceptions of the way data is used.

Jeanne: Tēnā koutou katoa. I’m on Dale’s team, and I’m the Senior Advisor who’s been part of the journey toward developing the algorithm charter over the past year. Now, I’m leading the thinking about how we implement the algorithm charter. I’m really pleased to have this opportunity to chat with you today to share more about our work and what’s behind it, and where we’d like to take it into the future.

Faun: For our readers who are unfamiliar with the idea of an algorithm charter, would you mind giving us your elevator pitch version of what it is and what it does?

Dale: Yes, of course. The algorithm charter came out of our Algorithm Assessment Report, which looked at what algorithms were being used across government. The charter is a commitment by government agencies to improve consistency, transparency, and accountability in their use of algorithms. It does that through the areas specified in the charter, which are transparency, partnership, focus on people, data, privacy, ethics, human rights, and oversight. We launched it in July of this year, and there are currently 26 signatories across government who have made a commitment to apply the charter to their work as kind of a best-practice standard. It’s a work in progress. We know technology is evolving fast and we know that it’s not necessarily the perfect solution to the challenges that we face, but we see it as an important step in a journey.

Figure 1: Statistics New Zealand, Algorithm Assessment Report, Oct 2018, p. 32.

Faun: Would you mind putting the number of signatories into context for us? How many agencies are there in New Zealand, and how many more are you looking for to sign on?

Dale: Yes, the 26 signatories are more than half of all the central government departments in New Zealand. And so far, the list does include almost all of our large data agencies, by which I mean the agencies who either use a lot of data in their work or are big consumers of data. And it also includes most of the social sector agencies who deal with the public.

Our hope is that our progress with this group becomes visible so that other people can see how it’s working. We’d like have more agencies come on board and sign. We are aware that some agencies are still working through what the charter might mean for them, like law enforcement agencies. We just recently had the New Zealand Police sign the charter, which is obviously a welcome development (New Zealand just has the one national police service). I hope that this will be a good example for some of our other enforcement agencies who are in the process of deciding if they’re going to sign the charter. I think the fact that they’re thinking it over means they’re seriously considering the implications, and we’re quite heartened by that because it means that they’re really considering how they would change their practice rather than just signing something for the sake of signing it.

Faun: I imagine that getting to develop the charter was a bit of a long road. Have you both been involved in a charter from the ground up? Can you tell us a bit about its development over time, and what kind of feedback you solicited and received?

Jeanne: The first step was to receive ministerial endorsement to develop a charter. We met with a group of digital and data ministers who agreed that this way of working would be good for New Zealand’s government and citizens.

Dale: It’s taken us a little over a year to develop. To develop it, we worked with agencies first, and then we developed a draft charter, and then we went out and consulted with the public for a couple of months in 2019. It was open to public submissions to hear what people thought about the draft that we had.

The main points of feedback we got related to making sure that Te Ao Māori (Māori worldview) perspectives are actually embedded in the charter in a way that is appropriate for government agencies. There were also a lot of submissions focused around how it would be implemented, which was entirely reasonable and appropriate because this is unknown territory to some extent. We were also asked some questions about scope. Initially, we were trying to define algorithms in some kind of meaningful way. But really, I think submitters felt that a fixed definition would constrain the work, or not work for some group of agencies, and obviously we’re aware that the technology is moving and changing. That’s why we ended up with the Risk Matrix, which I think we’ll talk about a little later.

The charter responds primarily to the need for more consistency in the way that agencies are using advanced analytics like algorithms. The Algorithm Assessment Report found that there are pockets of good practice and there is also room for improvement. Within government, there’s obviously a bit of a tension between how we ensure that this responds to the recommendation of consistency, without wanting to stifle innovation. The really important thing is to achieve some basic level of consistency across all our departments and agencies because we tend to be quite siloed in the way we do things, so we designed the charter to fit within our current accountability mechanisms and arrangements.

In the end, agencies are making this commitment, although they are already accountable in many other ways to the public, to the parliament, and to our various regulators who keep an eye on things.

Faun: Did these submissions come from the private sector as well?

Dale: Yes, we got a couple of the big tech firms who provided responses. We also had academics, NGOs, and then people who are just generally interested in the topic and the subject. It was a good diversity of perspectives and opinions.

Jeanne: Overall there was general support for working on this and for building consistency in how government uses algorithms. I think the substance of the submissions was how you do that. There was no questioning around whether or not this is the right thing to do. We found that encouraging.

Faun: As you know, Canada has recently released a Directive on Automated Decision-Making and Algorithmic Impact Assessment tool. Did you engage with Canada or any other countries during your charter development process? If yes, what kind of lessons were shared by the international community?

Dale: We engaged with the Office of the Chief Information Officer in Canada about the various different approaches that we’re taking in an attempt to achieve similar kinds of things. And here we also have bilateral meetings with countries like Australia, as well as also other countries in the Open Government Partnership network like the Netherlands and France, who also have similar challenges or actions under the Open Government Partnership framework that they’re looking to advance. We’re always interested in what they’re up to. A lot of people are looking around, seeing what possible solutions exist. I think the question that most jurisdictions are grappling with is how you translate data ethics ideas into action and practice.

Jeanne: I think the Canadian model is really interesting. I suppose the caveat for all of this is that it’s an evolving technology and an evolving field, as is the cultural environment that a technology is deployed into. So I think there’s not going to be one solution that you can lift and drop into every country. However, it was really helpful to have that kind of interaction with our peers overseas. I suppose in all of this work, we recognize that it’s developing and that this is a real opportunity for us to participate in a meaningful global dialogue.

Dale: Yeah, I agree with all of that. The OGP work is interesting because it spans a lot of different international jurisdictions in terms of size. And obviously for us and our situation, we’re not dealing with a decentralized federal model with states and territories; as a central government we’re relatively agile.

Faun: You mentioned the Risk Matrix earlier as a way to assess algorithms without having to narrowly define them (or which ones might have impacts worth assessing). Could you talk a bit more about the Risk Matrix tool and how it will work for signatories?

Dale: Well, we’re still working through it, to be honest. As I mentioned before, we’re only about two months in, and figuring out what knowledge we’ll have to share with agencies to help them use the Risk Matrix tool. The report I mentioned earlier covered 33 different algorithms that the agencies described as being significant in terms of their impact on people. So those are good case studies of algorithms that would probably, as the agency defines them, fall under the charter.

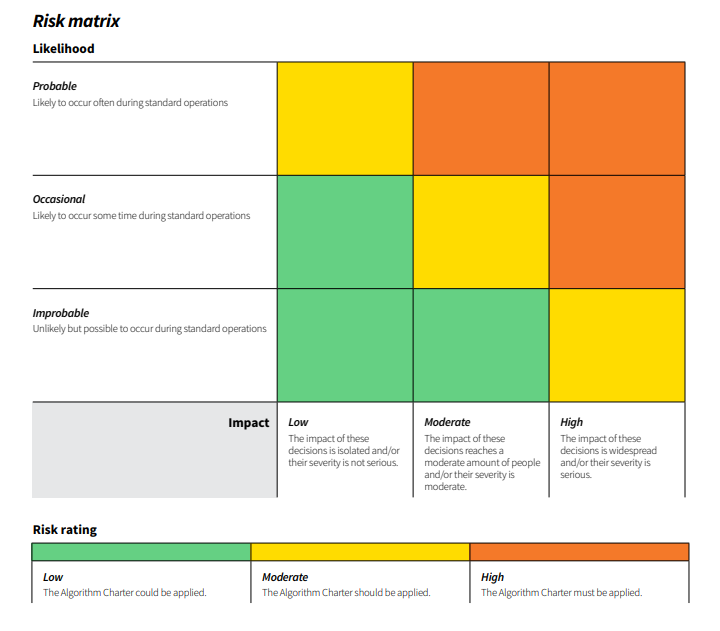

Jeanne: The idea is that when an agency signs up to the charter, they would make an assessment using the Risk Matrix of all of their algorithms or families of algorithms. And then, based on the rating within the Risk Matrix, they apply the commitments as appropriate. What the assessment looks like will be different for everybody, but that’s the process that we expect agencies to work through.

Figure 2: Risk Matrix, Algorithm Charter for Aotearoa New Zealand, Statistics New Zealand, July 2020.

Faun: You mentioned earlier that many of the public submissions you received involved making sure that a Te Ao Māori perspective was respectfully included. The final version of the charter commits to embedding a Te Ao Māori perspective in the development and use of algorithms consistent with Treaty of Waitangi principles (for unfamiliar readers in North America, Māori and English versions of the founding treaty of Aotearoa New Zealand were signed in 1840). Could you comment on what this means?

Dale: This is a journey that the Government of New Zealand itself is on. The principle of Te Ao Māori also features in our new public service act, which sets expectations for all public servants. And that’s really about making sure that you’re bringing Te Ao Māori or Māori worldview to concepts, knowledge, values, and perspectives. You’re bringing Te Reo Māori, which is Maori language, into your work as much as you can. You are respectful and mindful of Tikanga Māori, which is about cultural practices and understandings. And you’re thinking continuously about the day-to-day operation of partnership principles. You will see that in the charter on one level. We’ve also signalled at other complex issues happening in the space, like Māori data sovereignty or, in the wider world, Indigenous data sovereignty. The charter also acknowledged that some of those things are beyond the scope of a document like this. They still warrant proper attention, but this is probably not the vehicle for that yet.

Jeanne: As Dale mentioned, we’re really encouraged to include Te Reo Māori, the Māori language, in our work. So one thing that we have done with the charter is publish a Māori language version as well, and provided all of our agencies across government with an English language version and a Māori language version to show that we’re completely committed to working in this way. And we hope that that’s starting on the right foot. There’s a commitment around the Treaty of Waitangi, which as you know is a constitutional document for New Zealand, that the public expect us to be doing this as well. That was something we heard really clearly from the public submissions.

Faun: Moving on to some of the charter’s comments on transparency and peer review, the charter suggests “clearly explaining how decisions are informed by algorithms.” Could you comment on whether this also means that AI should be “explainable” (in other words, does it preclude “black box” solutions from being used in government applications)?

Dale: Our perspective on this is that people should be able to understand the role that the data and analytics — advanced analytics included — play in making decisions that affect them, whether they’re specifically about services or, at a broader level, about prioritization or even environmental concerns. We think that is something that should absolutely be explainable by a government department or agency without needing to go into the complexity of the data itself or the way that the AI has interrogated the data to derive an outcome.

By far and away in the New Zealand context, there are hardly any cases where there’s a completely automated decision happening. It’s almost always informing a human’s judgment. That said, the role that the data is playing in that space should be absolutely transparent to the public when a significant decision is being made. We think that is pretty unambiguous and not something that’s too hard for agencies to get across. It doesn’t necessarily mean you have to be able to explain the technical stuff. But from our perspective, and the charter kind of alludes to it, we think it would be good practice for people working in government agencies who have the technical skills and are interested to be able to go into some of the detail as well.

Faun: Thank you, and the charter also makes a very interesting recommendation about regular peer review of algorithms for unintended consequences. Could you comment on how you intend to implement that? Who will be doing the peer review?

Dale: We’d like to start thinking about pulling together a group of experts that agencies can call on — experts who are outside of government, independent, and who have the right expertise and tools to support reviews throughout the procurement process and afterwards. Obviously, the key is going to be in the application of the algorithm over time in terms of checking for those biases.

It will be interesting to see how that progresses, to look back over time and see what the outcomes would be like, compared to what you would have expected.

Faun: You began to answer this already, but I’d like to ask about how the charter will impact procurement.

Dale: In the New Zealand context, we found through the Algorithm Assessment Report that we don’t really buy a lot of off-the-shelf algorithms. We really are too small and our populations are too different and specific for most off-the-shelf algorithms, which are designed largely in North America and for North American populations. What we tend to do is buy solutions and then customize them, using human decision-making, for our particular context. So we are looking for agencies to embed the charter when they are doing that process of customization.

That said though, the Algorithm Assessment Report did have some other recommendations that were specifically about procurement, and we’re working with our partner agencies, the Department of Internal Affairs and the Government Chief Digital Officer, on those.

Figure 3: Statistics New Zealand, Algorithm Assessment Report, Oct 2018, p. 34.

Faun: Building on the topic of procurement — is there any interest in extending something like the algorithm charter to the private sector in New Zealand, or implementing any kind of regulatory framework?

Dale: Our conversations with ministers in this space have been around the idea that the public service needs to get its house in order first and sort out its algorithms before we’re in a position to start telling the private sector how to do its business. Obviously, there are a lot more complex issues when you get into privacy, proprietary knowledge, and those kinds of things.

However, we’re pretty keen to see more uptake of this within the New Zealand context. So the flip side of your last question is that we still have more scope to expand. We’ve got over half of our core central departments, but then there are a lot of crown entities and other kind of quasi-government organizations who also might fit into the public sector, along with local government. There’s still quite a bit of ground to cover in terms of the government side of the coin before we go to the private sector. But we’re already quite heartened by hearing private sector organizations talk about how they’re trying to align their work with the charter, even though they haven’t signed it and they’re not required to sign it at this time. I think what we’re trying to do is say this is a good way of doing things and it’s not necessarily complete. But if you’re serious about it, then this might be a thing to start thinking about, especially in circumstances where the government might be procuring your services.

Faun: Absolutely, thank you. And a final question, I can’t help noticing that you’re sitting side by side in an office — I feel like I haven’t seen that in a very long time here, with many people in North America working from home! We’ve seen a lot of international news about New Zealand containing COVID-19 quite quickly, so have you noticed it impact your work at all, or has it not been on the radar?

Dale: Absolutely. We’ve been working on the charter in conjunction with a number of other data ethics pieces. So when COVID happened here, there was a huge focus on data and the need for data-driven decision-making in terms of impact and modeling. As an agency and as a government, we all support that effort because it was obviously what we needed to do to keep people safe. And what we know from our perspective, thinking about these issues, is that it’s probably more important than ever to incorporate data ethics into that stuff because what that showed us is that we need more data. We need better data in order to be able to model and forecast, and especially for specific populations who are quite vulnerable, such as Māori and Pasifika people in New Zealand, or people with disabilities.

And if we’re going to involve more data in that space, a big part of that is making sure that the public trusts the government with their data and to make informed decisions. In my opinion, the pandemic is a great example of where that really counts. There’s never been a more important time for ethics to be built into our work.

Faun: Thank you very much for that. In closing, is there anything you’d like to comment on that I didn’t ask you about?

Dale: We think ethics and algorithm transparency are global, they’re borderless, and they impact both the public and the private sector. And we clearly think that there’s only going to be growth in the world of data. I mean, you don’t have to be a genius to see that this is where the world is going. And so, therefore, complex issues like ethics and the kind of things that the algorithm charter addressed is how people see themselves in this new world, and how people can trust the way that governments deal with their data and mobilize the data in a meaningful way to help them and protect them and support what they want. This means that countries are going to have to come up with tools that are going to work for them. Our charter works for us. But we think that it won’t necessarily be the same-size-fits-all for each country.

I think the other thing, the other big lesson we take out of this, is to iterate and be prepared to be flexible. We’ve learned throughout the development journey that you can’t just sit and forget these things. They have to be living, and you have to continue to engage with people. How you drive to a solution that can benefit everyone is the hard work, but it is the hard work that’s necessary for us to get the benefit of all this technology that we want to use because otherwise you run the risk that people stop giving you the data or opt out. And that’s not really good for anyone, I think, in terms of society.

Jeanne: I definitely support everything that Dale has said around the importance of data ethics as a global issue. I want to mention quickly that the algorithm charter isn’t the only thing that we’re doing. We’re also working with tertiary education [post-secondary for North Americans] providers here in New Zealand to develop a micro credential around data ethics. We’re considering how we prepare the workforce in New Zealand to make decisions in an ethical way, which we think is really important. The Government Chief Data Steward has also convened a data ethics advisory group, an independent group of experts who can consider proposals for new and innovative uses of data from the New Zealand government, similar to the charter’s independent peer review. So we’re working away at practical support for ethics in government here in New Zealand. We’re really pleased to be able to have the mandate and the space to be able to do that and also to have opportunities like this to talk about them and make connections across the world.

Dale Elvy is the Manager of the System Policy team at Stats NZ (the national statistical organisation of the New Zealand Government) leading the team that supports the role of the Government Chief Data Steward. His focus in the public service has been on the interface between data and policy, and he has previously worked for New Zealand’s Ministry of Education in roles spanning policy development and evidence, data, and insights. Dale holds a PhD in political science from the Australian National University and a Master of Strategic Studies from Victoria University of Wellington.

Jeanne McKnight is a Senior Policy Advisor in the System Policy Team at Stats NZ where her work has focussed on building public trust and confidence in government use of data. She brings a focus on other cultures and contexts to her work, having previously worked in the international relations field for the City of London and the Wellington City Council. Jeanne has a Bachelor of Arts in Modern Languages and Art History from Victoria University of Wellington and holds post-graduate qualifications in business and Mandarin.

ICTC’s Tech & Human Rights Series:

Our Tech & Human Rights Series dives into the intersections between emerging technologies, social impacts, and human rights. In this series, ICTC speaks with a range of experts about the implications of new technologies such as AI on a variety of issues like equality, privacy, and rights to freedom of expression, whether positive, neutral, or negative. This series also particularly looks to explore questions of governance, participation, and various uses of technology for social good.